Until 1900

We can distinguish, in the history of architecture (and art in general) in France, three main periods: first, ancient architecture, which was brought by the Greeks, and was combined with Gallo-Roman art; then Christian architecture, which extended from the fifth to the sixteenth century, embracing Latin art, Romanesque art, and ogival or Gothic art; and finally, Renaissance architecture and modern architecture, which, with its eclecticism, is more and more a European and world architecture and less and less an architecture that can be called French.

Antiquity.

The Greek colonies of the south of Gaul brought their architectural system: one sees, at the bottom of Vernégues, near Pont-Royal, the ruins of a Greek temple; the museums of the cities of the South of France contain steles, altars, and other objects of this time. The Romans spread throughout Gaul their legions of soldiers and workers, and covered it with their monuments. Today we can still admire these prodigies of construction which have survived so many centuries: the bridges of Saint-Chamas, Sommières, Vaison; the aqueduct of Nîmes known as the Pont du Gard; the aqueducts of Lyon and Metz; the gates of the cities of Saintes, Nîmes, Autun and Carcassonne; the Thermal baths of Cluny, Paris, Saintes, Nîmes, etc. the triumphal arches of Orange, Carpentras, Reims, Saint-Remy, Cavaillon; the theaters of Lillebonne, Orange, Vienna; the amphitheaters of Nimes, Arles, Saintes; the square house of Nimes, the palace of Constantine in Arles, the Gallien palace in Bordeaux, the temple of Livia in Vienne, the temple of Riez; the funerary pyramid of Couard near Autun, and that of Saint-Remy; finally, among the military constructions, the tower of César, in Provins.

The architecture of the Middle Ages

Christianity did not modify Roman architecture at first; it adopted its forms and rules until the 11th century. The first Christians were obliged to take refuge in underground tunnels to celebrate in secret the ceremonies of their worship: these first churches or crypts are generally small, without any other decoration than some rough paintings. The crypt of the church of Ainay in Lyon, that of Saint-Gervais in Rouen, and the church of Saint Paul in the old cemetery of Jouarre, can give an idea of these primitive monuments of Christian art. When Constantine allowed the Christians to celebrate the mysteries of their religion in freedom, they built oratories and churches on all sides, modest constructions made on the model of the Latin basilicas, which gave this first Christian architecture the name of Latin style. The Franks and the other Germanic tribes, by settling in Gaul, did not modify the artistic system which they found in use there: they thus accepted the Latin art, as they took the religion, the language and the manners of the Gallo-Romans. Until the 8th century, the constructions were small, mostly made of wood, with a decoration of a summary taste. The still existing monuments of the Merovingian period are: the church of Saint-Jean in Poitiers, which dates from the 5th or 6th century; the church of Savenières, whose frontage and nave are of the 6th or 7th century; the church of Saint-Jean in Saumur, and the Basse-Oeuvre of Beauvais, which date from the 8th.

With Charlemagne we see the appearance of the Byzantine domes, and the rounded forms of the funeral church of Jerusalem, of Saint Sophie in Constantinople, and of Saint Vital in Ravenna. The relations of the great emperor with Italy and the East gave architecture new tendencies; but his reign is too short for art to take fixity and a precise determination, and, after him, new darkness covers France. The monuments which remain to us from the Carolingian period are several churches of Aix-la-Chapelle, Cologne, and Nijmegen, the church of Sainte-Croix in Saint-Lô, Notre-Dame d’Orbieu, the churches of Orcival, Issoire, Vermanton, Saint-Nectaire, Nantua, the abbeys of Fontenelle and Tournus, ! The church of Saint-Bénigne in Dijon, the church of Saint-Martin in Angers, the Manécanterie in Lyon, and the crypt of Saint Denis, near Paris.

However, one should not consider these long centuries of hesitation and trial and error as sterile: a slow but continuous work of transformation is taking place, and when times become better, when calm is restored, one is astonished to see mature ideas, new and learned forms being produced

The Romanesque architecture.

After the year 1000, Romanesque architecture developed almost instantly in all its beauty. It seemed, according to the expression of a contemporary chronicler, that Europe was stripping itself of its rags to put on the white dress of churches. There are still some Byzantine reminiscences, but the plan of the basilica has been modified: no more apsidal sanctuary, no transept without choir, no isolated naves: the sanctuary and the choir are joined and lengthened; apsidal aisles and radiating chapels surround them; the transept is moved back and forms only the head of the aisles to leave more place to the faithful; the plan took the shape of the Greek or Latin cross; the sculpture begins to deploy its richnesses with the portals. The art takes, moreover, a national character: while the East preserves types and hieratic rules in the religious representations, the Occident places in its monuments the costumes and the national types, which follow the modifications of the taste of each country.

The monuments of Romanesque or Romano-Byzantine style are numerous in France; we will quote among the most remarkable the churches of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris, of Saint-Père in Chartres, of Saint-Sernin in Toulouse, of Sainte-Croix in Bordeaux, of Saint-Étienne in Caen, of Saint-Étienne in Beauvais of Châlons-en-Champagne, of Noyon, of Saint-Georges de Boscherville, of Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire, of Vézelay, the lower parts and the crypt of the cathedral of Chartres, the portals of Saint Trophime d’Arles and of Notre-Dame de Poitiers. At the same time, buildings of a different kind, imitated from the Greek art which developed in Saint-Marc in Venice, rose in some provinces, similar to those seeds removed by the winds and which give birth to trees foreign to the countries where they were carried: One of these curious buildings is the church of Saint-Front in Périgueux, an exact copy of the church of Saint Mark, and which probably served as a type for the cathedrals of Cahors and Angoulême, the abbeys of Solignac and Souillac, and perhaps the cathedral of Puy.

It should be noted that the major provinces of France each had a particular school and style. As early as the 10th century, schools of architecture were established in the convents: they were exclusively dominated by the Greek schools, whose wealth lent itself wonderfully to the luxury displayed in the churches. But, in the twelfth century, St. Bernard thundered from the pulpit against this luxury; then a split broke out: the school of Cluny retained the richness of the Byzantine style, while that of Cîteaux, returning to simplicity, to severity, abandoned the luxurious forms. This last school prepared and brought the Ogival style in its beautiful simplicity.

From the XIIth century, the architectural schools can be recognized by the difference of the materials they use and the style of their monuments:

- the Ligerian School, which developed along the Loire, in the Blaisois, Touraine, Anjou, Maine and Poitou; it is distinguished by the elegance and the profusion of the ornaments which it threw around the doors and the windows, on the walls, the friezes and the capitals, such as scrolls, garlands, bouquets, branches charged with leaves and fruits, flowers, drawings in arabesques, by the solidity of its vaults in full arch, by the size, the choice and the regularity of the apparatus;

- the Aquitanian School, which preserved with tenacity until the XIVth century the Romano-Byzantine style, and which, remarkable, like the preceding one, by the purity and the elegance of its sculptures, employed only exceptionally the broken chevrons, the meanders, the chessboards or checkerboards, the broken torus, the rhombuses and all the angular mouldings, preferring the rounded and flexuous lines;

- the Auvergne School, whose members, devoted only to the religious architecture, were entitled the lodgers of the good God, the monuments which it raised offer rarer and less pronounced buttresses than in the North, columns less short and less collected than those of the primitive Romance, not very developed towers, little richness in the mouldings, a decorative marquetry with the archivolts, with the pediments, with the circumference of the apses, finally of small and persistent arcatures

- the Burgundian School, which kept the fluted pilasters of ancient architecture;

- the Norman School, the most important, the most fertile, the purest of all alloys, inferior in relation to ornamentation as long as the Romanesque-Byzantine style lasted, but which took off in the ogival period, and whose monuments, of vast proportions, were crowned with beautiful square towers and slender spires.

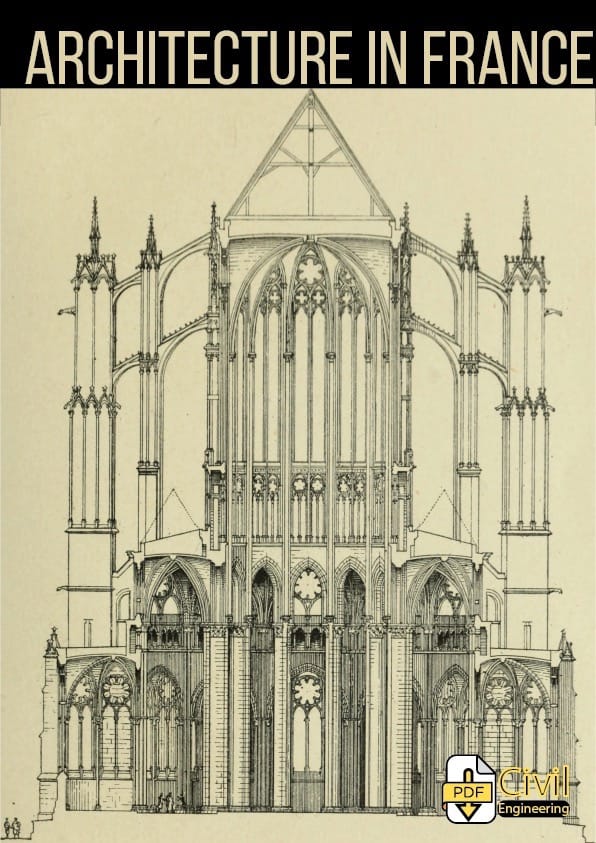

Gothic architecture.

Until the 12th century, architects borrowed their decorative system from abroad, and they kept the vaults and round arches of Antiquity. A new form appears; it is the ogive, which is called to operate a radical revolution. Whatever opinion one adopts on the origin of this new form, it seems certain that the first application of it was made in France, and that the artists were the first to understand all the advantage that one could draw from it. From the first half of the twelfth century the ogive makes its appearance: we see it in the portal of Saint-Denis in 1140, in that of Chartres in 1145, in the choir of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in 1163, in that of Notre-Dame de Paris in 1182. The oldest monuments of the transition, those where we find the primitive ogival (or gothic) art, are found only in France; it is an established fact. The first ogival church of England is that of Canterbury, which dates from 1174 and was built by a Frenchman, Guillaume de Sens; the cathedral of Cologne is posterior to those of Amiens and Beauvais, and traced on their plan; the church of Wimpfen-en-Val was built from 1263 to 1278 by a Frenchman; the cathedral of Prague is due to Mathieu d’Arras and Pierre de Boulogne, and that of Upsala in Sweden, to Pierre Bonneuil, stonecutter of Paris; Philippe Bonaventure and Mignot, both of Paris, raised the Dome of Milan, and Hardouin the church of Sainte-Pétronne in Bologna. The Gothic style lasted about three centuries; it is divided in France into the primitive ogival or lancet style (from 1150 to 1300), the radiant ogival style (from 1300 to 1400), and the flowery ogival or flamboyant style (from 1400 to 1550). The most remarkable monuments of these three periods are

- the cathedrals of Paris, Reims, Chartres, Rouen, Amiens, Bourges, Beauvais, Noyon, Soissons, Laon, Sens, the abbey of Saint-Denis, the Saints of Paris and Vincennes;

- Saint-Ouen of Rouen, Saint-Urbain of Troyes, the portal of Saint-Antoine (Isère);

- Notre-Dame-de-l’Epine, the great portal of the cathedral of Rouen, the church of Saint-Maclou of the same city, the spire of Strasbourg, the nave of the cathedral of Nantes, etc.

The military architecture began to take a rapid rise towards the 11th century, and the country was covered with fortresses. We can judge of their importance by the splendid debris which still remain, such as the ramparts of Aigues-Mortes, Arles, Avignon, Carcassonne, Die, Montpellier, Narbonne, Saint-Guillhem, Provins; the doors of Moret, Cadillac, Nogent-le-Roi, Saint-Jean de Provins; the castles of Alluye, Argental, Blanquefort, Angers, Beaucaire, Bruniquel, Chalusset, Château-Gaillard, Coucy, Chinon, Fougères, Cesson, Montlhéry, Mehun, Loudun, Pierrefonds, Saumur, Vincennes, Le Vivier; the castle of the Popes in Avignon, the Palace of Justice in Paris; the fortified abbeys of Saint Jean-des Vignes in Soissons and of Saint-Leu d’Esserant; the fortified bridges of Cahors and Aigues-Mortes, etc.

The civil architecture did not remain behind, and a good number of cities still preserve houses of these times.

History has been able to record only a few names of the artist-builders of the Middle Ages; among them, we shall mention : Romuald, architect of Louis the Debonair, who began in 840 the cathedral of Rheims, rebuilt later; the bishop of Chartres, Fulbert, who gave the plans of his cathedral and directed the first constructions; the abbot Suger, who had the abbey church of Saint-Denis rebuilt according to his own plans; Robert de Luzarches and Thomas de Cormont, architects of the cathedral of Amiens; Pierre de Montereau, architect of the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris; Robert de Coucy and Jean d’Orbais, architects of the cathedral of Reims; Jean de Chelles, one of the architects of the cathedral of Paris; Eudes de Montreuil, who built in Paris the churches of Sainte-Catherine-des-Écoliers, of the Hôtel-Dieu, of Sainte-Croix de-la-Bretonnerie, of the Cordeliers, of the Blancs-Manteaux, of the Mathurins and of the Carthusian monks, all of which have been destroyed; Jean Ravy, who finished the church of Notre-Dame; Hugues Libergier, architect of Saint-Nicaise de Reims; Jean Langlois, architect of Saint-Urbain in Troyes; Enguerrand le Riche, architect of the cathedral of Beauvais, etc. It is towards the end of the XIIIth century and during the XIVth that these companies of masons, carpenters and sculptors were formed, to which the Freemasons owe their origin. It is also then that, in the South of France, the Pontifical Brothers built the bridges of Avignon and Pont-Saint-Esprit, wonderful works for this time.

The architecture of the Renaissance

At the end of the 15th century, the artists of Italy had repudiated the traditions of Gothic architecture, and were successfully engaged in the study of Antiquity. The work of the Renaissance, i.e. the return to antiquity, was less rapid in France. Painting and part of sculpture frankly followed the new ways; but architecture and monumental sculpture tried to maintain the ogival forms; they increased excessively the ornamentation, and, by overloading it with pretentious and tasteless details, hastened its decadence.

Such was the situation, when the French were led in Italy by Louis XII. Georges d’Amboise, ardent promoter and enlightened protector of the arts, wanted France to benefit from the marvels of Italian art, and brought a famous architect, Fra Giocondo, a Dominican monk. There was no lack of artists, but they were still building in the flamboyant style, despite their marked tendencies towards the Italian style; such were, in Rouen, Roger Ango, architect of the law courts, Pierre Desaulbeaux and the Leroux brothers, architects and sculptors of Notre-Dame and Saint-Maclou; in Solesme, Pilon the Elder; in Troyes, François Gentil; in Nantes, Michel Columb; in Orléans, François Marchand and Viart; in Tours, Pierre Valence and Jean Juste. Giocondo had only to direct the talents of our artists towards the Italian style, and we soon saw the charming palace of the Court of Auditors in Paris, destroyed by fire in 1737, and the splendid residence of the Cardinal of Amboise in Gaillon, of which Pierre Valence was the architect and Jean Juste the sculptor.

The eastern facade of the castle of Blois also dates from Louis XII. However, some artists, faithful to the old style, built the castles of Vigny and Châteaudun, the town halls of Nevers, Arras, Saint-Quentin, the pretty little chapel of the Hotel de Cluny, and the Hotel de La Trémouille in Paris. During the reign of Francis I, Serlio and Vignole, called to France, made the principles of Vitruvius and Palladio triumph, at the expense of Gothic architecture, which was definitely condemned. Serlio rebuilt the castle of Fontainebleau, which Primaticcio and Rosso decorated inside. Dominique Cortone (Boccador) built in 1533 the City Hall of Paris; Then one saw the great façade of the castle of Blois, the castles of Madrid, of La Muette, of Saint Germain, of Villers-Cotterets, of Chantilly, of Follembray, of Nantouillet, of Écouen, of Varengeville, of Azay-le-Rideau, of Chenonceaux, and the one of Chambord, a kind of compromise tried by Pierre Nepveu between the two rival styles.

Castle of Blois.

The civil architecture had quickly yielded, and without too much difficulty, to the demands of fashion, especially since the Italian style lends itself better than the ogival style to the interior layout of the houses; but it was not the same, for the religious architecture. Jean Texier continued to build the northern spire of Chartres Cathedral; other architects built the church of Brou, the central spire of Notre-Dame and the Butter Tower in Rouen, the Saint-Jacques-la-Boucherie Tower in Paris, the spires of Saint-André in Bordeaux, of Saint-Jean in Soissons, etc. The chapels of the castles of Chenonceaux, Blois, Nantouillet, Écouen, are in the ogival style, while all the other parts of these castles are in the Renaissance style. Philibert Delorme was the first to build the chapel of the castle of Anet in purely Italian style, in 1532.

There were protests against the use of foreign architecture in religious monuments, for example, the spire of the cathedral of Beauvais, built in 1555 by Jean Wast and François Maréchal (it collapsed in 1573), and the churches of Saint-Etienne and Saint-Eustache in Paris. But these efforts were in vain: a revolution had taken place in people’s minds since the 15th century, religious beliefs had weakened: the Greco-Roman orders prevailed, and Vitruvius became the true leader of the French schools. Then rose the pavilion of the Clock and the left wing of the Louvre, the fountain of the Innocents, on the drawings of Pierre Lescot; the Pont Neuf, the hotels Carnavalet and Bretonvilliers, the great gallery of the Louvre, under the direction of Jacques Androuet Ducerceau; the new castle of Saint-Germain en Laye, today destroyed, of which J.- B. Ducerceau was the architect; a facade of the castle of Fontainebleau, by Jamin; the palace of Luxembourg and the portal of the church Saint-Gervais, by Debrosses; the beautiful lighthouse known as the Tower of Cordouan, built by Louis de Foix.

The architecture of the modern times

The XVIIth century.

In the 17th century, during the administration of Richelieu and Mazarin, Renaissance architecture lost its grace and delicacy; it became heavy and dragged itself painfully into the ancient rut. Some architects, however, stand out: Charles Lemercier builds the Sorbonne, the Palais-Royal and a new wing in the Louvre; Pierre Le Muet and François Mansart erect the Val-de-Grâce; Louis Le Vau builds the Collège des Quatre Nations (today the palace of the Institut de France); and Louis Le Vau is the founder of the Institut de la Ville de Paris. the palace of the Institute of France), completed the Tuileries with the architect d’Orbay, and built the castle of Vaux; Gérard Désargues gave the drawings of the Hôtel de Ville de Lyon, which another architect, Simon Maupin, had the glory of building.

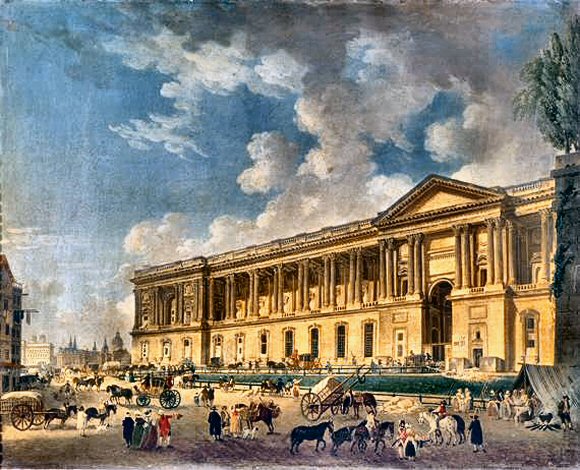

Painting by Pierre-Antoine Demachy.

Architecture, under the reign of Louis XIV, emerged from the hesitations it had always had, whether it affected a lightness that was often more astonishing than thoughtful, or whether it bent under the heaviness of the proportions; henceforth sure of itself, it became learned, full of grandeur, majesty and unity. It is still Antiquity, but serving only as a basis and model for the proportions and the purity of the details. Two great facts contributed to this important progress, the creation of the Academy of Architecture, founded by Colbert in 1671, and the publication of the principal ancient buildings of Rome, measured and drawn by Desgodets, on the order of the same minister, in 1682. The first eight members of the Academy were Blondel, Le Vin, Bruant, Gittard, Le Paultre, Mignard, d’Orbay and André Félibien. The castle of Versailles and the church of Invalides were built under the direction of Jules Hardouin Mansart, the colonnade of the Louvre and the Observatory of Paris became the glory of Claude Perrault, Blondel built the Porte Saint-Denis, Bruant built the Hôtel des Invalides and went to England to build the castle of Richmond; Saint-Cloud, Trianon, Marly, are embellished with modern buildings; finally Antoine Le Paultre is occupied with the interior decoration of palaces, and draws the waterfall of Saint-Cloud. In all these works, wealth is combined with grandeur and majesty. Simon de La Vallée made Sweden adopt the French way.

The 18th century

The impulse given to architecture under Louis XIV was so strong, that it was felt during almost all the duration of the following reign, and that the architects maintained themselves for a certain time at the height of their predecessors. Robert de Cotte, father and son, built the colonnade of Trianon and the church of Saint Roch; Gabriel built the colonnades of the Place de la Concorde, the Military School of Paris, the opera house of Versailles and the castle of Compiègne; Soufflot built the church of Sainte Geneviève (Panthéon), the Law School in Paris, and the great hospital in Lyon; Servandoni made the portal of the church of Saint-Sulpice. Other French architects, Peyre, Jardin, de la Guépière, Thomas, Thibaut, etc., built abroad the palace of Coblence, the cathedral of Copenhagen, the palace of The Hague, the city hall of Amsterdam, the great theater and the Stock Exchange of St. Petersburg, etc.

However the purity of the taste had been altered in Italy; Borromini and his school had thrown themselves in a system of exaggerated, tormented, pretentious ornamentation; they did not delay to find imitators in France: Oppenord was the chief of this new capricious and whimsical school, which gave birth to the style known as of Louis XV, and whose type is the marvellous residence of Mrs Dubarry in Luciennes. Boffrand, an architect of the same school, decorated the Hotel de Soubise (now the National Archives), the palace of Nancy for King Stanislas, the residence of Wurzburg, and the castle of the Favorite, near Mainz. In the monuments of this period of art, one must recognize that the grace, the delicacy, the unexpectedness and the originality of the ornaments make forgive what is incorrect, irregular and false.

After Louis XV, there was a turnaround in the minds of the people: a lively ardor for the ancient arts was revived; the discoveries of Pompeii and Herculaneum gave an irresistible force to these new tendencies, prepared by the learned writings of Winckelmann. Boullée in architecture, like David in painting, was the leader of the new school. Among the architects of this severe period, we will quote: Gondouin, who made the School of Medicine of Paris, Ledoux, who built several beautiful hotels in Paris, among others the hotel of Thélusson, in front of the street of Artois, and the barriers of Paris, today destroyed (Propylées de Paris). destroyed (Propylées de Paris); Louis, to whom we owe the galleries of the Palais-Royal, the French Theater, the old Opera, and the theater of Bordeaux; Wailly, architect of the room of the Odeon in Paris; Rousseau, who gave the plans of the hotel of Salm (today hotel of the Legion of honor); Chalgrin, who built the Collège de France and the church of Saint-Philippe-du-Roule; Antoine, who built the church of the Monnaies and the Palais de Justice in Paris, the palace of the prince of Salm-Kiburg in Germany, the Hôtel de la Monnaie in Bern, and the palace of the duke of Berwick in Madrid. We can mention in second order Detournelle, Hubert, Van Clemputte, Poyet, Beaumont, Renard.

Under the First Empire, then under the Restoration, architecture was limited to copying Antiquity; it lacked grandeur and originality. Fontaine and Percier were the leaders of the schools of this time. The triumphal arch of the Étoile was built under the direction of Chalgrin, the Bourse under that of Brongniart, the column of the Place Vendôme with Gondouin and Peyre, the arch of the Carrousel with Fontaine and Percier, almost all the interiors of the Louvre by the same two; the palace of the Corps législatif (Palais Bourbon) by Poyet, the palace of the Conseil d’Etat and the Cour des Comptes, on the Quai d’Orsay, by Lacornée; the church of the Madeleine by Vignon and Huvé, etc.

The 19th century.

In the XIXth century, the French architects return to more correct and wiser ideas; if they do not have a style of their own, at least they do not repudiate any, and we do not give themselves up to any slavish copy; they restore with care and purity the monuments of all times, they seek the best advantage to draw from the various styles. It is the eclecticism which imposes itself. The government of Louis-Philippe raised the column of July on the place of the Bastille and the palace of Fine Arts. Under the reign of Napoleon III, public works took off in a big way: we will mention the completion of the Louvre, the extension and construction of the street of Rivoli, the boulevards of Sebastopol and Malesherbes, the development into English parks of the woods of Boulogne and Vincennes. The French school of architecture in this period is represented by Lepère, Huvé, Achille Leclère, P. Debret, Blouet, Lebas, Duban, Hittorff, Visconti, Lassus, V. Baltard, Labrouste, de Gisors, Lefuel, Viollet-Le-Duc, etc. (E. L.).