Transfer of biological criteria of life to architecture – spin off

The transfer of biological criteria of life to architecture requires discussion of areas, where biology and architecture actually meet. Instead of staying in the centre of each discipline, the boundaries have to be explored – in order to find that these fields are not as distinct as they seem to be.

The examination of the overlapping fields will hopefully result in further mutual understanding, convergence of disciplines and common action.

2- BACKGROUND

For this interdisciplinary investigation it is necessary to define and describe the fields of both architecture and biology to provide the essential background.

2.1 ARCHITECTURE

“[Architecture is] the art or practice of designing and constructing buildings…

The complex or carefully designed structure of something”

The second definition taken from the New Oxford

American Dictionary already characterises the “nature” of architecture. The discipline that puts material or immaterial things in order is called architecture in many fields, not only in the classic architecture of building. There is a basic architecture in the design of life and organisms, and even in information technology we use the word architecture when describing the basic layout of computer programs.

What is architecture? What is not architecture? About projects, constructions and structures

Architecture is interpreted here as a widespread profession engaged in the design of the built environment. It includes design on all levels of scale, from urban and regional planning to small building projects. It is not exclusively referred to as “proper” architecture, which is designed by architects, but as a general term standing for the material structure that defines space and enables interaction.10 Architecture contains life. As Kaas Oosterhuis says, “architecture becomes the discipline of building transactions”: it is about to move beyond containing activity, taking an active role, not only influencing but interacting with living systems.

Making architecture is about making projects.

“Project” has a wider meaning than a common intention or plan to do something. In architecture, projects are building tasks, which may already have been completed, or are still in “project phase” existing on paper (or encoded on hard disks), waiting for realisation, or having been already abandoned.

The term does not refer to a specific size or scale.

As innovation is the focus in this discussion, we will also take into account unbuilt projects, if they are important to illustrate developments in architecture.

Some unbuilt projects became very famous in architecture history as exemplary designs. Being unbuilt, and often described only roughly, these projects on one hand still provide space for vision, and on the other hand the basic idea is not yet spoiled and watered down by the needs of execution. Frederic Kiesler’s “Endless house”, for example, was never built, but served as a kind of asymptote for many other attempts at organic space. Buckminster Fuller’s visualisation of a transparent dome over Manhattan is tempting for anyone dealing with lightness in design, but still impossible to realise.

The exactitude of expression is difficult to maintain in the process of application and execution, but this is also one of the big challenges in architecture.

Most interesting in the context of biological paradigms for architecture are projects which show a strong interrelation between form, function and structure or construction, so load bearing is a key function and will therefore be focused on.

“Construction” and “structure” are commonly used for elements of architectural projects which have to fulfil tasks of load bearing. The differentiation between construction and structure is somehow connected to that of structure and material.

Following Jim Gordon: “Structures are made from materials and we shall talk about structures and materials; but in fact there is no clear-cut dividing line between a material and a structure.”12 In common use, a construction is something which has to be put together, typically a large element.

The term structure is used in a more abstract notion, when we are talking about load bearing for example, but can as well be used for any important ordering element (which could be abstract), or a discernable pattern, even surface patterning.

2.1.1 Which architectures are important in this context?

When focusing on development and progress, we have to think about tradition and technology as well as innovation and experiment. The architectural examples which will be used to illustrate the theoretical framework cover the gap between traditional building typologies that have developed over a long time and new designs that contain innovation of some kind. Many projects have come to be classic examples for their time or the technology they represent.

So when considering an imaginary scale of innovation, the two extremes are interesting: the typologies, where innovation has almost come to an end in a long optimisation process, and the projects, advancing development and innovation.

Case studies performed by the author or done under her guidance will be used to explain specific aspects of a biomimetic approach to architecture in detail.

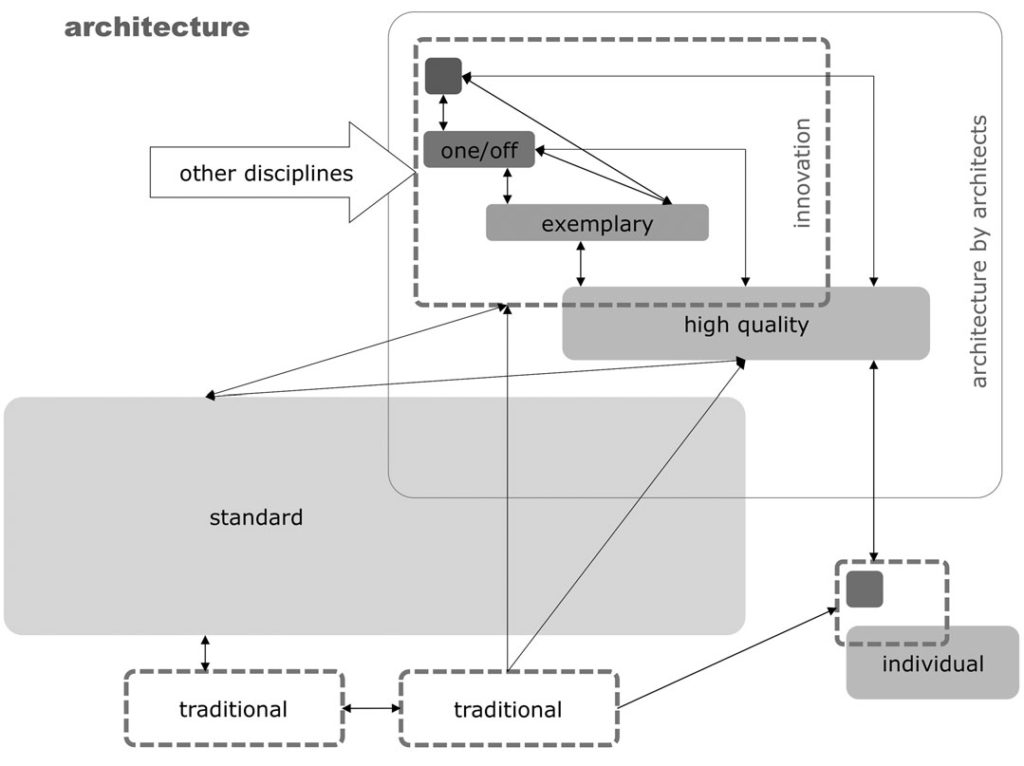

2.1.2 Categories of architecture

Only a small part of all built environment is designed by architects. Unfortunately, architects tend to restrict themselves to “proper architecture”, which confines their influence.

There are many ways of categorising architecture in order to get a general idea of this huge field. We could use the scale of the project, the function of the building, the quality of the building, the region where we find it, the tradition or singularity, the construction method, the material used, the style, the date of building, and so on. All these categories overlap, and it is difficult to count or even estimate the number in each category. In the course of this discussion, “scale” will often be used for categorisation.

Difference in scale implies different boundary conditions and thus different planning and development processes. For this reason, the categories “urban design”, “building”, “process” and “material” will be used for a comparison with criteria of life, and will then be explained in more detail.

Other categories will be applied when needed.

The most important aspect for categorisation when asking about innovation and progress is the innovativeness implemented in a project.

Quantification is not possible within the frame of this book. The categories’ qualities are described and examples are mentioned. Figure 1 (opposite) shows architectural categories referring to a specific scale of innovation.

“Architecture of provision” is the lowest possible stage and is not identified in the scheme. Shelters are made of whatever can be used and no formal planning process is used. Today, unplanned settlements and slum architecture exist predominantly in warmer climate zones. Out of necessity and pragmatism, traditional architecture typologies have developed in a long empirical optimisation process. Traditional building typologies differ according to environmental conditions: society, climate, landscape, resources, technological standard, historical development and other influences. These typologies form the base for further development. All architecture is based on tradition: historical building typologies which have evolved over a long time, and which slowly adapted to the changing environmental conditions of the time, although these conditions may no longer exist.

The so-called “one-off projects” are singular phenomena in architecture. As the term says, their existence is a singular stroke of luck. The circumstances under which the implementation of such a project is possible include a visionary mind, the success of the technology being implemented, the necessary resources (ideally unlimited), excellent engineers, the support of the client as well as the support of society in terms of acceptance (building laws, political decisions). One-off projects are also well known by the general public, and judged by history. Few buildings become extraordinarily famous, e.g. the Centre Pompidou in Paris (Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano), Lloyds in London (Rogers) and the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank in Hong Kong (Norman Foster), the Cupola of the Reichstag in Berlin (Foster). Some of these also become public landmarks of design, symbolising countries or even continents, for example the Eiffel Tower or the Sydney Opera House. These buildings represent a high-tech approach of a global architectural style.

The innovation realised in these projects makes them role models for many other exemplary and high-quality buildings. The inventions (architectural features which can not be patented or otherwise copyright protected) developed in the course of the generation of these projects inevitably spread and become general knowledge, to the resentment of one and the delight of the other designer. Many renowned architects experiment on this 1:1 level, using their building tasks to develop specific ideas and push industry ahead.

Between these extreme positions the large field of “standard architecture” exists. Standard architecture covers a wide range of quality from high to low standard. This mass building (housing, office buildings, industrial…) is to only a small extent architect designed, and does not usually deliver outstanding experimental innovations.

Innovation achieved in this field concerns industrial economy, often conflicting with quality.

A small section of individual buildings show outstanding innovative potential – isolated visionary phenomena, designed by individual house owners or small companies.

Apart from that, innovation that raises quality usually occurs only in the upper upper right segment of Figure 1. The information flow between these categories of architecture is mutual.

Innovation from other disciplines and new technologies influences architectural development and is integrated into one-off or exemplary projects. Information then spreads slowly down to standard buildings (e.g. point fixing in glass, fingerprint access control – features which are now common even in single family housing). Innovative architecture is in many cases also influenced by traditional typologies – it is known that many famous architects have travelled extensively and studied traditional buildings typologies.

Occasionally, information of the individual section is taken up and spread into other fields. This is especially interesting, as these outsiders’ achievements are often based on and integrated into a local environment.

Small field: experimental architectural research

Experimenting with building tasks is the usual way for developing new solutions, but makes life hard for architects, companies and clients. Only small steps can be taken, and any innovation has to comply with specific building regulations, still provide security and functionality for the users, must have the same quality as the standard solution, and must not require extra resources. The planning costs for the design innovation are usually not calculated – the architect or designer and the building companies have to cope with this “loss” and all the dangers which a new solution may bring.

Strategic experimental research would require a platform free from the restricting 1:1 condition. Due to the lack of interest and funding, experimental design research is done by very few people and organisations. It is usually done at universities in the course of design programs, diploma and dissertation projects. Research bodies are funded if either the pressure to find new solutions is high enough to provide the necessary resources, or if economic success is expected in the near future.

2.1.3 Where biomimetics comes into play

The connection between architecture and biology and the starting points for biomimetics in architecture are in the design of projects, where innovation is needed, especially in cases like these:

- Design of architecture for new environments

- Solutions for new challenges have to be found, based on role models provided by nature

- Investigation of optimised and adapted building traditions informs modern architecture

- Better relationship between architecture and living organisms

- Better relationship between architecture and the environment

- Better quality of life

- Better design of the cultural environment

New challenges always push the boundaries: in the case of architecture it is the discussion about environmental issues (climate change, energy and resources, ecology and sustainability) and the need to cope with new environments which will shape the architecture of the 21st century with the help of nature’s role models.

2.1.4 The many levels of a project

An architectural project is designed to fit many different and often conflicting requirements. The ultimate demand is to provide sheltered space for the user’s activities.

However, other than basic functional levels of design are not limited to: external and internal circulation, the relationship between privacy and public access, visibility and transparency, construction and material, colour, light and surfaces, supply systems and infrastructure, building physics and building services, detailing, intangible things like general idea, abstract concept, geometric order, aesthetic concept, style, significance of the building to its surroundings, functional and aesthetic relationships to the environment including flows of energy and matter, urban and regional planning issues, ecological issues…

The architect’s task is the integration of all these levels in the final project. The value that the designer attributes to the different topics and the relative importance of the topics for the final project is part of the freedom of design and the individual approach to architecture in general. The significance of the topics considered and their relative importance for the given task is not always decided consciously, but chosen through personal intuition, and they may be ousted by the complexity of project development.

The factors responsible for the project’s final “identity” can differ widely. And wide is the field of application of any novel idea – from highly detailed items to large urban structures.

The quality of the final project is also defined by the quality of investigation conducted in the important stages of design.

2.1.5 Quality in architecture

The question of architectural quality is a complex and difficult one. To judge seriously the overall quality, for example of a building, all the levels of design mentioned above would have to be evaluated and compared. The assumption that architecture projects can be compared requires a more or less linear scaling, and the existence of a “best design”.

Considering the difference in levels of design and the difficulty of assessment of aesthetic values, this is not possible. A holistic evaluation would, on the other hand, imply an agreed value and defined relationship of all parameters that can be measured. Thus, overall quality is not measurable, and this may be the reason why evaluation of architectural projects is not at all taken for granted.

But specific qualities are very well measurable. For instance, energy processing of buildings is a serious current issue, as is the amount of embodied energy in building materials. Measuring is not limited to the world of matter and energy, but is also possible for activity and intangible parameters. The space syntax theory of Bill Hillier, for example, measures the value of “integration”, which expresses a kind of urban importance of a space.

Summing up, it can be said that evaluation in architecture is not routine at all, and that even simple checks (e.g. the assessment of the internal circulation of a building) are not often carried out, so that consistent quality enhancement usually does not exist. Another reason for this is the individuality of architecture projects in contrast to product design in industry, where high quantities justifies the implementation of quality control.

For these reasons, it is generally the market size that decides on quality, and the criteria remain largely unexplored. The measured parameter is market price per m2, which provides no information about resources and energy, nor about architectural quality.

2.1.6 Innovation and expectation

Expectation is a key to occupant satisfaction. The image of architecture in the user’s mind settles his interpretation of space and potentials of activity.

Obviously, unexpected events are not likely to be appreciated (e.g. malfunction, disorientation because of unclear spatial relationships), but slow change is. The capacity of humans to deal with new situations is amazing, but doing so costs time and energy. Relying on the well-known makes the day-to-day routine (and advancement in many other fields) possible, but palls at the same time. The happy medium has to be found – introduce the new and unexpected, but not too much at a time, so that people have a chance to change their minds.

There are solutions in architectural design which have proved to work out very well. Here the introduction of novel ideas would lead to a decrease in quality. Nonetheless many architects continue to reinvent the wheel.

Satisfaction of users is crucial to the success of architecture as a discipline, which creates, forms and organises people’s lives. The lack of connections between planners and users leads to continuing misinterpretations. On the other hand, integration of users into the planning process can be very difficult in terms of decision-making, time and therefore cost (regardless of the fact that the user’s opinion does by no means guarantee satisfaction). As a matter of fact any field that can reasonably be influenced by the future user’s wishes has to be defined clearly, as well as those fields where future users will have no say. The distinction relates to hierarchical levels in design, which will be explained later.